Will the death of the caliph determine the definitive disappearance of Isis? No, because today, the importance of the leader has greatly diminished in a slow but inexorable change of the fighting spirit.

by Silvia Scaranari

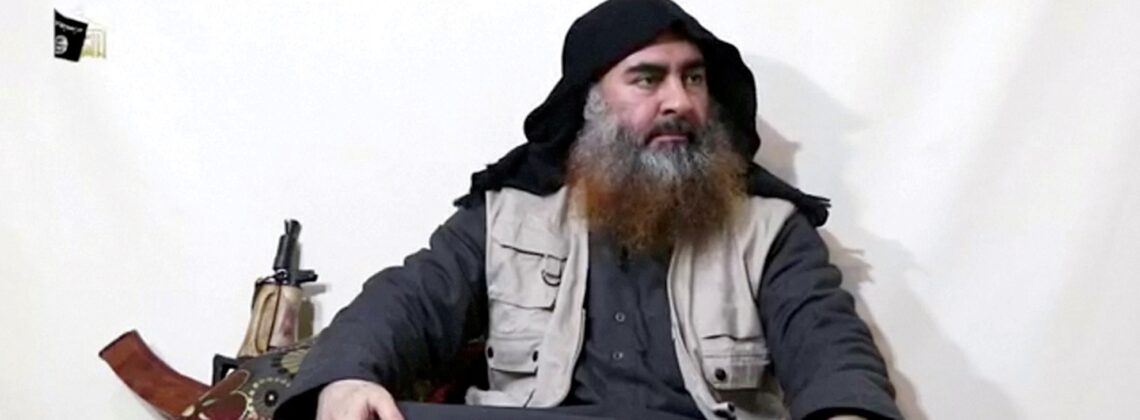

It is very recent news, even if somewhat overshadowed by the Sanremo Festival and its tail of controversy, that the leader of the Islamic State, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi is dead. The event took place during a maximum-security operation – as President Biden called it – by the United States Special Forces aimed at capturing important members of Isis. The raid partially failed because Abu Ibrahim blew himself up to avoid capture, and 13 other people died with him, including some children, probably close family members.

Abu Ibrahim al-Hachimi al-Qurayshi was, of course, only a pseudonym, artfully constructed to play the role of leader, as his predecessor al-Baghdadi had already done. In truth, Amir Mohammed Abdul Rahman al-Mawli al-Salbi had changed his name to be in the Prophet’s line of descent. Ibrahim refers to descent from Abraham, the great Father of the monotheistic faith, al-Hachimi to the Prophet’s clan, whose grandfather was Abd al-Muṭṭalib al-Hāshimī, and al-Qurayshi to the great Quraysh tribe, to which the Hachim clan belonged and which was dominant in Mecca at Muhammad’s birth.

Contrary to the vaunted prophetic lineage, Abu Ibrahim was born in Tal Afar, 50 km west of Mosul, descended from a Turkmen family. His father, a Sunni preacher, had provided him with a good university education and he had become an acute connoisseur of the Koran and the Sunna. As a young student, he joined the Ba’ath party and became an officer in Saddam Hussein’s army. After the death of the rais, he joined al-Qaeda groups, in particular that of al-Zarqawi, who had taken the place of Bin Laden in Iraq.

Arrested, he ended up in the Camp Bukka hard prison, a real “Jihad Academy” for the number of future Islamist leaders who were trained in its cells, where he met al-Baghdadi. It was probably here that his radicalism grew to the point where he joined the Islamic State when it was proclaimed in July 2014, after his definitive secession from al-Qaeda,

Having become a loyalist of the self-proclaimed caliph, after his killing in an American raid, he became his successor on 31 October 2019.

The Shura Council, a kind of assembly of wise men, recognises Abu Ibrahim, already indicated by al-Baghdadi, as the legitimate Caliph of the Islamic State.

Known for his determination and his very tough stance towards all the “enemies of Islam”, and despite the fact that the press release of his appointment contained an invitation to all fighters to swear allegiance to the new Caliph, “he did not have the international stature of the previous Caliph” writes Niccolò Locatelli in Limes.

Isis resists but in a very small area between north-west Iraq and Syria, exactly where it was born, and has been heavily decapitated in its leadership by the victory of international forces. The local populations, which perhaps initially supported the experiment of a shariah state, are today much colder, and a great many ‘mujaheddin’ are in captivity. The assault on the Ghwayran prison at al-Hassaka in Syria, last January, demonstrates the pressing need for men on the part of Isis.

Also significant is the place where Abu Ibrahim was hiding: the city of Atma (Atmeh) in the Idlib region, a few kilometres from where three years ago a similar operation led to the death of his predecessor al-Baghdadi. Situated close to the Turkish-Syrian border, this region is now said to be territory under Turkish custody and since the end of 2021 has been a sort of “residence zone” for thousands of Syrian refugees, in fact a huge refugee camp obviously paid for by the European Union. Nevertheless, what is most interesting here is that for years the Idlib region has become the final destination of the so-called “humanitarian corridors” through which – as the ISIS strongholds fell – militiamen were allowed to evacuate with their families, always conveniently in tow. In this way, the area became a de facto reserve for the dozens of militias that emerged from the fragmentation of ISIS. Some of these militias have begun to attack the Turkish army on the border in recent months, so much so that it is not difficult to imagine an informative contribution by Turkey to the operation against Abu-Ibrahim.

However, a question arises: why does this no man’s land continue to exist? Why have the allied forces not completed their mission to erase this reality of violence, genocide, abuse and violation of the most basic human rights?

The strength of Isis in the Middle East has greatly diminished, but a remnant continues to resist. The hope of creating a permanent Islamic State in the area faded a long time ago; many aspirations have moved to the Far East – see Indonesia – and, above all, to Central-East Africa, where, however, Jihadism has changed skin, has grafted itself onto organized crime and on corruption with large multinationals for the control of energy resources, and has lost the ideal of purity and territorial sedentariness.

Isis, with the many branches that have derived from it and with the most diverse names, has become more elusive but no less dangerous. The Jihadists who continue to be trained in the Middle East, in Africa, in Asia, and very often in Europe, continue to be dangerous, even though perhaps they no longer have the strength for extensive attack maneuvers. They have the danger of men who do not want to accept the defeat of a project and who are full of slogans that they no longer know how to relate to a profound content.

Saturday, February 5, 2022